The Long Game: Why We Endure the Absurdity of Test Cricket

1,289 words5–8 minutes

Try explaining the concept of Test cricket to someone who has never seen it, perhaps an alien observer or a confused American. You tell them that two tribes of humans will gather in a field for five consecutive days. They will stand under the scorching sun for thirty hours. And at the end of this grueling ritual, there is a very high probability that the result will be a “draw”, no winner, no loser, just an anticlimactic cessation of hostilities.

They will give you a stare of a million doubts. How is this an efficient use of energy? How is it fair to the bowler, who runs in ball after ball, tearing cartilage in their knees and grinding their shoulders to dust? How is it fair to the batter, risking broken fingers and fractured ribs against a hard leather projectile moving at 150 kilometers per hour? And how is it fair to the spectator, who invests five days of their finite life watching this slow-motion drama?

Yet, this inefficiency is precisely the point. Test cricket survives not because it is thrilling in the TikTok sense of the word, but because it mimics the biological and psychological reality of Homo sapiens. It is a test of resilience.

The Biology of “Staying Power”

In the last five years, the sport has produced moments that feel less like games and more like mythological epics. We saw India, humiliated after being bowled out for 36, rise from the ashes to breach the fortress of the Gabba in Australia. We saw New Zealand defeat India to become the first-ever World Test Champions. We saw South Africa’s Kagiso Rabada tear through Australian defenses with a five-wicket haul.

These are not just athletic feats; they are case studies in psychological endurance. According to research on elite performance, success in such long-format events depends entirely on “psychological resistance to long-term work.” Resilience here is not a fixed trait you are born with; it is a dynamic process. It is the ability to get knocked off balance (physically and mentally) and repeatedly adjust your thoughts and behavior to keep functioning (Hill et al., 2022).

The cognitive load is immense. Test cricket requires sustained attentional focus for hours on end. While mental fatigue usually degrades physical performance, elite endurance athletes have evolved an “adapted capacity” to invest mental effort even when their brain is screaming at them to stop (Martin et al., 2018); (Brown et al., 2016).

But cricket adds a cruel layer of social complexity: dependency. You can bowl the spell of your life, but if your batter fails, you lose. This creates a deadly psychological loop of frustration. This is where the tribe comes in. Resilience in cricket is a “dynamic group process.” It relies on clear structures, a shared “mastery approach” where setbacks are viewed as data rather than failures, and “social capital”—the family-like bonds that prevent the group from crumbling under multi-day stress (Morgan et al., 2019).

The Mirror of Life

Why do we obsess over this “fiasco” of a sport? Because, as the commentator Harsha Bhogle astutely observed, Test cricket mimics life. Life is not a T20 match; it is not a two-hour movie with a clean protagonist and a predictable climax. Life is a long, messy HBO series. It has subplots, character arcs, and long periods where nothing seems to happen. Until suddenly, everything happens. Sometimes mortgage rates go up; while sometimes we are just brisk-walking through existence.

Like any global human interaction, cricket is also a stage for our cultural misunderstandings and biological imperatives.

Consider the story of Javagal Srinath, an Indian fast bowler who toured in the 90s. While his international counterparts feasted on local cuisine, Srinath carried a pressure cooker in his kit bag. Why? Because he was a vegetarian, and the chicken sandwiches provided at lunch, perfectly normal in England or Australia, were a taboo in his culture. He had to adapt his survival tools to a foreign environment.

Or take the absurdity of Harbhajan Singh being detained at an Australian airport because his cricket spikes were dirty. To the Indian mind, this was silly; to the Australian customs officer, the soil on those shoes was a biological threat to the local ecosystem (Dawn, 2002).

Language, too, plays a treacherous role. In India, calling a mischievous child a “monkey” is an affectionate admonishment. When Harbhajan Singh used that term for Andrew Symonds during a heated moment, he didn’t realize that across the cultural divide, in a country with a different history of race relations, he was using a racial slur. The intent was lost in translation, but the conflict was real.

The Substitute and the Predator

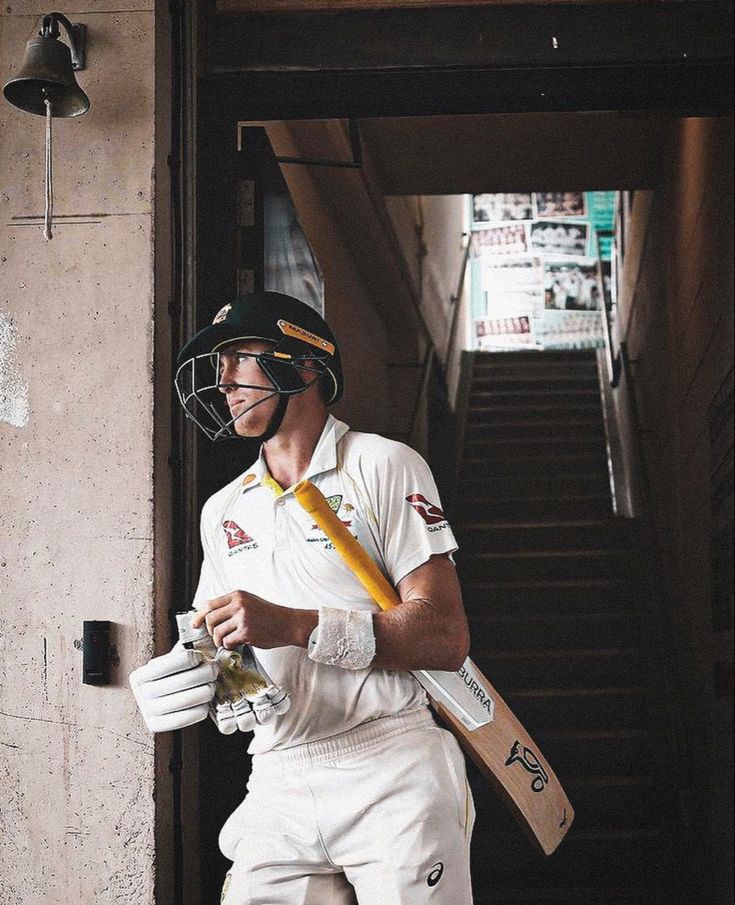

If you want a single image that encapsulates the survival instinct of the human animal, look no further than the Ashes series of 2019 at Lord’s. The narrative seemed written by a cruel dramatist: Steve Smith, the alpha of the Australian batting tribe and the best problem-solver in the game, had been felled. He was struck down by a violent, 92mph projectile from the arm of Jofra Archer. The crowd fell silent. The “king” was broken.

In any other era of history, the tribe would have been leaderless, the morale shattered. But the laws of the game had recently mutated to allow a new evolutionary adaptation: the Concussion Substitute.

Enter Marnus Labuschagne. At the time, he was not a star; he was a footnote. He walked out to the center not just to play a game, but to step into the bloodstained shoes of a giant. And what happened next defies the biological imperative of fear.

Archer, smelling fresh blood, steamed in and delivered the exact same delivery that had just hospitalized Smith. A 90mph bouncer. It smashed into the grille of Labuschagne’s helmet with a sickening crunch. The impact was in the exact same physical space where Smith had fallen. The stadium gasped. The narrative logic dictated that the substitute should crumble, that the predator had won.

Biologically, every neuron in Labuschagne’s body should have been screaming “Flight!” instead of “Fight.” But the human mind is capable of overriding millions of years of evolutionary programming. Marnus did not collapse. He simply popped back up. He adjusted his helmet, chewed his gum, and offered a look that spoke a thousand words. He signaled to the bowler: Well bowled. Next one, please.

It was a moment of absolute absurdity and absolute bravery. It showed that while the individual bodies are fragile, prone to breaking fingers and concussions, the collective spirit of the team can produce a replacement who walks into the line of fire and treats a life-threatening projectile like a minor inconvenience.

The Evolution of the Generalist

The game, however, is mutating. In the era of Sourav Ganguly, the Indian team practiced with the leisure of 19th-century aristocrats, tea for two hours, a heavy lunch, perhaps a nap. Today, players are the fittest organisms on the pitch.

I recently spoke to a friend who pointed out a fascinating anomaly: the current Indian team often fields three or four wicket-keepers in the same “Starting XI.” Why? Because the era of the specialist is dying. In the past, a fast bowler could be biologically useless with a bat, they were specialists. Today, the environment demands versatility. You cannot just do one thing. You must diversify your portfolio of skills.

Perhaps this is the ultimate lesson cricket offers us. In a world of increasing complexity and long, grueling challenges, specialization is risky. To survive the Test match of the 21st century, you must be resilient, you must rely on your tribe, you must be a generalist, and regardless of where you are going you should probably always carry your own pressure cooker.

Leave a comment